Madrid, 13 April 2015 – Access Info Europe welcomes the launch of the Italian version of the Alaveteli request platform, called “Chiedi” meaning simply “Ask!”.

The following article was originally published in the European Journalism Observatory’s website.

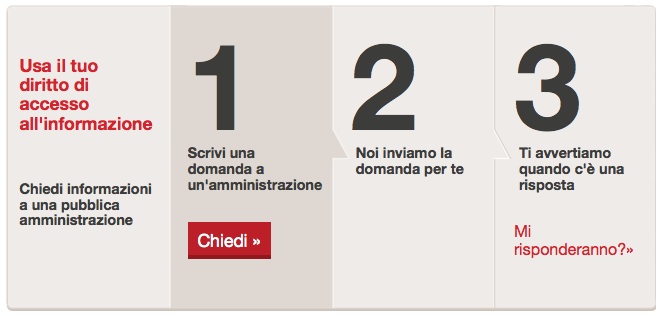

An online platform that enables citizens and journalists to send automated freedom of information requests to public bodies in Italy has been launched by Italian non-governmental organisation, Diritto di Sapere (Right to Know).

The platform, Chiedi (Ask), aims at making access to Italy’s public records and data easier, and at strengthening transparency and accountability in the country.

Chiedi is a “Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) machine”: a tool which simplifies the bureaucracy surrounding access to information legislation. “We want to offer a service to citizens wishing to send a FOIA request to an Italian institution,” said Guido Romeo, Diritto di Sapere’s President and Wired Italy’s data editor.

“Usually, the first problem is to find the right email address for where to submit the request. Our platform makes that much easier, as we have gathered the right contacts for each institution included,” Romeo said.

A second step that an Italian citizen, not familiar with local freedom of information laws, needs to complete when submitting a FOIA request is to ensure that it is correctly structured. “For this reason we think it is very useful to collect and show on the website all the requests that have been previously sent through the platform,” Romeo said.

In order to assist journalists and citizens to prepare a request, Diritto di Sapere has also released an online manual, LegalLeaks, which describes the legislation, and how to use it.

Chiedi, currently still in a beta phase, is developed on the Alaveteli software. This is coded by the British MySociety and is already used successfully in many countries. It allows users to select the recipient they want to get in touch with, then Chiedi addresses the email to the right contact.

Chiedi enables users to track the progress of FOIA requests

Users can also track the progress of their requests and browse examples of what other citizens have previously done, and evaluate the outcomes. “We don’t manage the requests directly as we don’t filter or regulate anything that comes through the platform. It is the open source software which does it all and the system also signals to requesters if an answer comes in, or if the legally required 30 days for answering has expired,” Romeo explained.

Similar websites already exist in 17 countries

A similar platform has been already launched by the British WhatDoTheyKnow website and in Spain by Tuderechoasaber and by the AsktheEU project, operated by Access-Info Europe. Globally, there are 17 countries where such a platform is available and 200,000 requests have been sent through these sites so far.

As well as the practical advantages of Chiedi and similar sites, there are also ethical benefits. “With Chiedi, we want to show what citizens ask for and what they actually get in response,” Romeo said. He added that after a few months of operation the site would also reveal which institutions respond well to FIOA requests, and which do not.

Chiedi should not be seen as a threat by institutions, but as a tool to better understand public expectations

Diritto di Sapere pioneered a similar survey in 2013 with the help of 40 volunteers when “The Silent State” report was published: “Chiedi will enable us to have a continuous and more ubiquitous monitoring,” explained Romeo. “I really hope Italian public bodies won’t see Chiedi as a threat, but rather as a tool to understand what citizens want and how to make their work better.”

Italy’s FOIA rules are complicated and technical, and journalists are not always aware of their rights

Diritto di Sapere also wants to evangelize about the opportunities the Italian freedom of information laws offer journalists, despite the weakness of current FOIA legislation. But are journalists aware of their rights?

Romeo believes they are not: “Journalism schools do not cover these issues and in newsrooms there’s usually one guy doing investigative work who’s also skilled in this sense. Moreover, while the US law is much easier to use, in Italy a certain expertise is required to ask for a document by quoting the right commas of the law. Response rate in our country is very low and this disincentives many. What we need to understand as journalists is that a public institution which doesn’t respond to lawful request is news worth covering.”

Italy ranks very low in the International Right to Information (RTI) rank. The country’s freedom of information laws date back to the 1990s and contain no reference to the Internet. Recent attempts to improve this did not have a serious impact. Even before the launch of Chiedi, Diritto di Sapere has been very vocal in pushing for the launch of a proper Italian FOIA by guiding the Foia4italy initiative which crowdsourced a law proposal, recently presented to MPs in Rome.

In the meantime, Chiedi is hungry to gather requests from citizens and journalists.

This article was first published on the Italian EJO website.